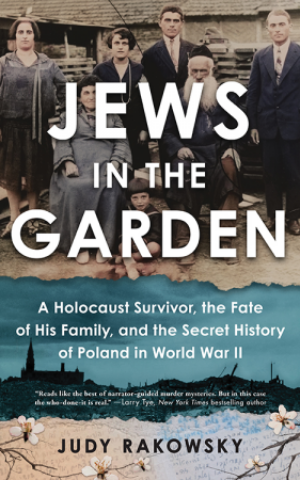

When investigative journalist Judy Rakowsky located the mass grave of five relatives murdered in the Holocaust, she and her cousin decided not to mark the site for fear of attracting vandals, grave-robbers, and irate townspeople. Instead, she wrote a book about them — and their probable murderers.

Published on July 11, “Jews in the Garden: A Holocaust Survivor, the Fate of His Family, and the Secret History of Poland in World War II,” follows Rakowsky’s inquiry into two sets of relatives murdered under mysterious circumstances near the end of World War II.

On a farm outside Kraków, five of Rakowsky’s relatives were murdered after hiding for 18 months. One of them — 16-year-old Hena Rozenek — escaped the massacre, and Rokowsky became determined to learn her fate.

As one eyewitness told Rakowsky about her relatives who hid on the farm, “[The family] were buried next to a big cherry tree. Each year, the tree bore fruit, but the cherries quickly turned dark. Everyone was afraid to eat them, thinking that they might be poisoned or cursed by the Jews buried below. Then the tree died.”

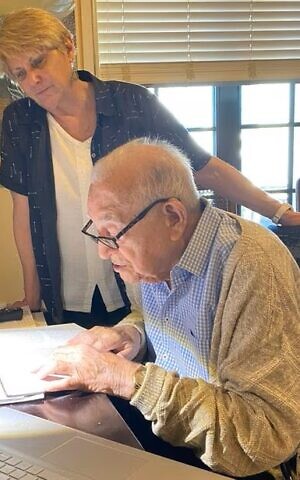

Pursuing dozens of leads across three decades of research, Rakowsky partnered with her cousin — 98-year old Holocaust survivor Sam Rakowski Ron — on nine research trips to Poland.

During their early visits to Poland, Rakowsky and her cousin gained increasing access to archival materials. In more recent years, however, the situation deteriorated significantly, she said.

“I had challenges getting records in this country. The change that came after the [Law and Justice] party took over was noticeable. It got harder,” said Rakowsky, a long-time reporter and editor for publications including People Magazine and The Boston Globe.

Early in “Jews in the Garden,” Rakowsky relays that Polish partisans — members of the Home Army underground resistance movement — were responsible for murdering her relatives. At one site, partisans forced the Jews to jump out of a second-floor window while shooting them to death.

After the war, some individual Home Army members received recognition from Yad Vashem for helping to rescue Jews. However, there are far more documented accounts of Polish “partisans” tracking down Jews in hiding and murdering them, whether for their valuables, their property, or antisemitic reasons.

“I wanted to be very faithful to the facts of the Home Army [in the book],” Rakowsky told The Times of Israel. “The Home Army didn’t have control over every sub-group. There were shifts in where they had control and where they did not,” she said.

From the seminal book, “Night Without End: The Fate of Jews in German-Occupied Poland,” Rakowsky learned of partisan massacres of Jews throughout the Kraków region, which includes her cousin’s hometown, Kazimierza Wielka.

“It is so grim,” Rakowsky said of the book. “The study of the county where my family comes from has not been translated into English. It’s soul-chilling,” said Rakowsky.

During the so-called Judenjagd (Jew hunt) phase of the Holocaust in Poland, Jews who survived deportation to Germany’s three “Operation Reinhard” death camps were captured by the Germans in collaboration with Polish authorities and — of pivotal importance — Poles who betrayed the location of Jewish hiding places.

In recent years, Poland’s government has pressed charges against historians who publish “defamatory” research on the activities of Poles during the Holocaust.

“Governments have gotten into the game of historical narrative,” said Rakowsky. “Ultimately, it is sad because the partisans’ achievements should be celebrated,” said Rakowsky, who plans to visit Poland with her cousin in September.

“We can’t only have history that’s like a Hollywood story, or we will never get past what took place,” said Rakowsky. “A lot of Poles want to celebrate the history of Jews who lived there and to know about it. And this gets in the way.”

‘They just wanted to live’

During the course of her fact-finding missions to Poland, Rakowsky relied heavily on her Holocaust survivor cousin to translate conversations into English. At one point, Sam told Rakowsky she was a “burden” and not needed on the next trip.

“When he pushed me aside a little bit, I became more engaged,” said Rakowsky, who eventually earned her cousin’s admiration for uncovering far more than was thought possible.

During the war, Sam Rakowski smuggled himself into the Kraków ghetto to escape capture outside the city. He was imprisoned at several forced labor camps and survived a death march from Sachsenhausen concentration camp outside Berlin in 1944.

Each time Rakowsky and her cousin visited Poland, they came back to the US with a few more pieces of the puzzle.

In personal encounters Sam had in Poland, said Rakowsky, her cousin wore his warmth on his sleeve, convincing people to open drawers at archives and unlock traumatic memories.

“We have gotten close to relatives of people who tried to save our family,” said Rakowsky.

One of the book’s subplots is the relationship between Rakowsky and Danuta Sodo Ogorek, whose grandparents hid Rakowsky’s relatives on their farm.

“It was shocking enough to happen upon a family of five buried in a working farmyard, not to mention discovering they were Sam’s aunt and uncle and three grown cousins,” wrote Rakowsky of locating the mass grave on the Sodo farm.

Astoundingly, the Sodo family is still stigmatized for attempting to rescue Jews, as explained by Rakowsky.

“The community had shunned her family, not only punishing her grandparents for trying to save five lives but holding a grudge against them for three generations,” wrote Rakowsky. “She brushed it off. It said more about them than her family, she said.”

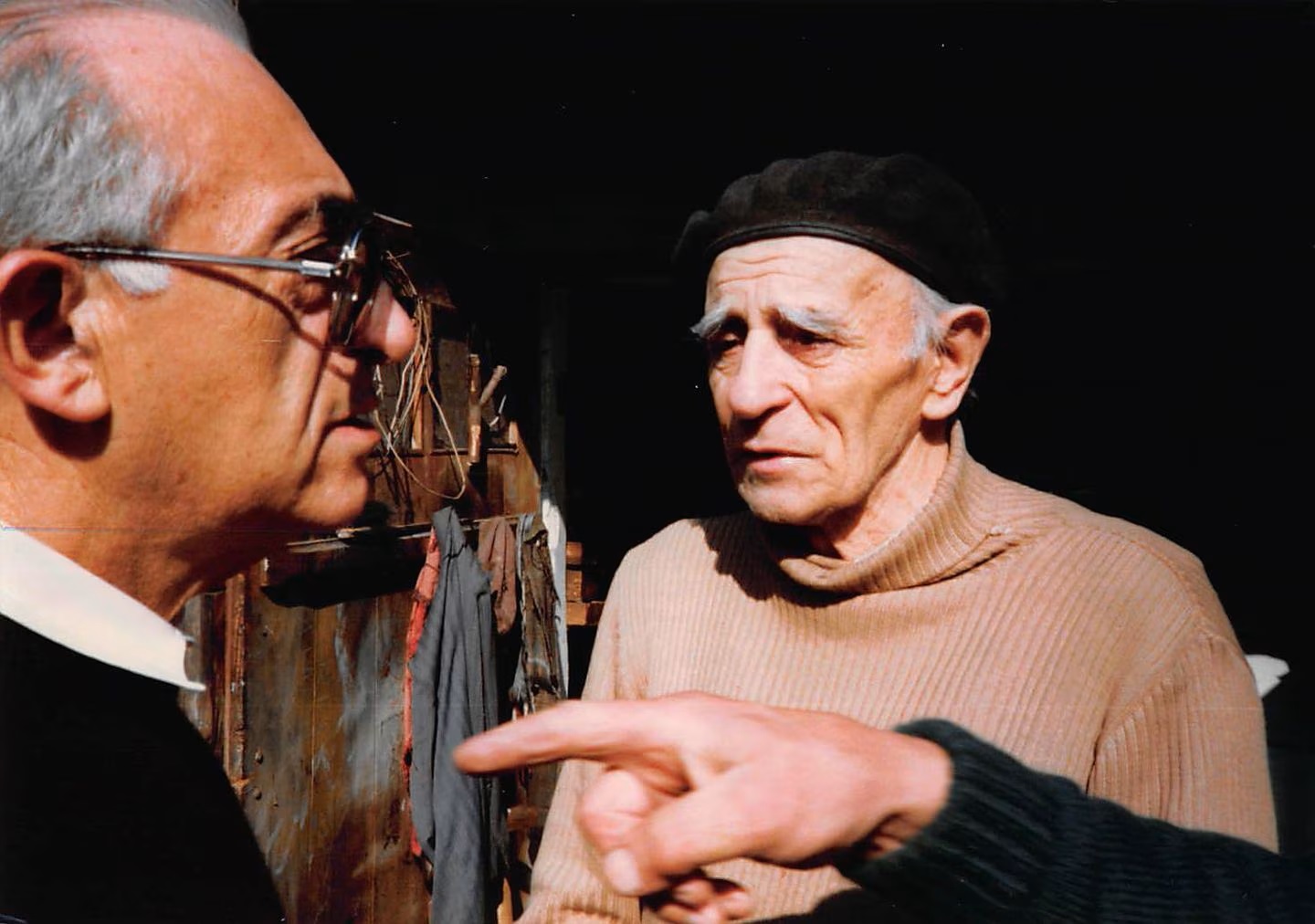

Finally, a major breakthrough came when a former Peasants Battalion leader tells Sam Rakowski that members of his group murdered the Rozeneks. (Judy Rakowsky)

Sodo, wrote Rakowsky, is guided by her family’s strong Catholic faith. But during Germany’s occupation of the village, neighbors grew to resent the Sodo family for hiding Jews, which neighbors said exposed the whole village to German reprisals.

“These Jews, your family, they just wanted to live,” Sodo told Rakowsky.

Long after the war ended, Sodo and her husband built a new house on her family’s farm. In choosing a site, they took into account the location of the mass grave where Rakowsky’s relatives were buried.

During one of Rakowsky’s more recent visits to Poland, she and Sodo spoke about why Rakowsky keeps returning to the country. For Sodo, there was no mystery to the question.

“Your people are here,” Sodo told Rakowsky, which catalyzed something within the investigative journalist.

“I shivered,” wrote Rakowsky. “No longer was I a tagalong or bystander. This land, these stories, were part of me now.”