Holocaust survivor Olga Czik Kay remembers not having a single menstrual period while imprisoned in Auschwitz, Kaufering (a sub-camp of Dachau), and Bergen-Belsen.

“My last period was at home in Ujfeherto, Hungary, before we were deported,” Kay recently told The Times of Israel.

Fortunately, Kay’s regular cycle returned as she convalesced in Sweden after the war, before immigrating to the United States at age 20. She later had no difficulty getting pregnant and had two children.

Researchers have found that over 98% of women ceased to menstruate immediately after arriving at Nazi concentration camps. The prevailing explanation for the phenomena has been the trauma and starvation they experienced.

The fact that Kay’s fertility returned post-war means her story is starkly different from the disproportionately high number of female Nazi concentration camp survivors who, according to a new studyhad difficulty regaining their periods, getting pregnant, and/or carrying fetuses to term. After immense suffering and the loss of many family members, these women were devastated that they were unable to have the large families they so desired.

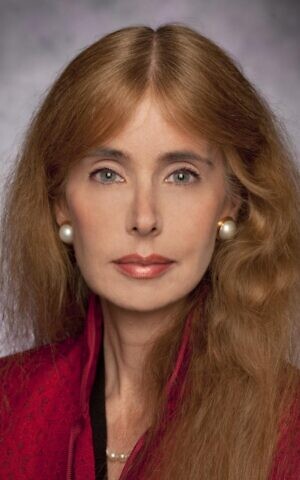

“They asked themselves, ‘Am I still a woman, will I be able to have children?’” said dr Peggy J. Kleinplatz a sex therapist and researcher on the faculty of the University of Ottawa’s School of Epidemiology and Health. Kleinplatz is the lead author of the new study, which proposes an alternate hypothesis for what caused the mass amenorrhea and subsequent infertility issues.

Dr. Peggy J. Kleinplatz (University of Ottawa)

According to the study, the uniformity — and uniformity of timing of cessation of menstruation — possibly point to the surreptitious administration of exogenous sex hormones (sex steroids) to female prisoners.

Among the 93 female survivors (with an average age of 92.5) interviewed by Kleinplatz for the limited study, were those who attributed the amenorrhea to something put in the food. Some recalled a floating white powder and rumors that it was a chemical called “brome” or “bromide.” (Other sources refer to similar recollections.)

A survivor from Belgium named Lilly Malnik told Kleinplatz that when she worked in the kitchens at Auschwitz for five months in 1944, she witnessed “packets of ‘grain-like, very, very light pink chemicals’ with the texture of ‘wet, kosher salt’ that were brought… by armed guards and dissolved in the rations so that ‘women don’t get their periods.’”

A female guard forced Malnik to empty packets of the substance into the vats of “soup,” which was distributed only to the women and not to the men inmates.

Kleinplatz surmises that the “chemical” referred to by the women could have been exogenous sex hormones, which had been synthesized in the early 1930s by German scientists chemist Adolf Butenandt and gynecologist Carl Claubergboth of whom joined the Nazi party. The hormones were manufactured by the German pharmaceutical company Schering and initially used to treat infertility among German women. Schering continued to manufacture synthetic estrogens and progestins in large quantities during the war. (The same hormones, depending on combinations and dosages can, can either treat or cause infertility.)

Defendants at United States of America v. Karl Brandt, et al. (also known as the Doctors’ Trial), Nuremberg, Germany from December 9, 1946, to August 20, 1947. (US Army photographers, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

“We don’t know exactly which steroids were given to the women in the camps and in what doses,” Kleinplatz told The Times of Israel in a recent interview.

The study cites records from the post-war Nuremberg Trials relating to evidence that the Nazis sought cheap, fast, and effective methods of mass sterilization of Jews.

Experiments were conducted at Ravensbrück and Auschwitz involving surgery, doses of high radiation, and injection of caustic substances into females’ reproductive organs.

But the Nazis sought to “produce a drug which after a relatively short time, effects an imperceptible sterilization on human beings,” according to an October 1941 letter from Nazi physician Adolf Pokorny to SS Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler. A follow-up memo to a July 1942 discussion between Himmler and his personal administrative officer Rudolph Brandt referred to “the sterilizations of Jewesses” and “a method which would lead to sterilization of persons without their knowledge.”

Jewish women from Subcarpathian Rus selected for forced labor at Auschwitz-Birkenau march toward their barracks after disinfection and head shaving. (Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

The details of this plan are not known because Himmler apparently instructed all those involved to keep it secret and not commit anything to writing.

Despite the doctors’ letters that were introduced in the trials, the idea of mass sterilization was not followed up on. Kleinplatz posits that since the birth control pill had yet to be introduced (it became available in 1960), prosecutors may not have known about the existence of the exogenous hormones. Or they simply were not aware that virtually all women prisoners stopped menstruating.

Kleinplatz thinks the latter possibility is entirely possible. In the mid-20th century, people kept their sexual lives and infertility issues private.

“The women spoke about it among themselves in the camps, but less so after the war when they were continuing with their lives and trying to start families,” Kleinplatz said.

Female prisoners during roll call in front of kitchen building at Auschwitz. Photo from ‘Auschwitz Album.’ (Unknown author, possibly SS officers Bernhard Walter or Ernst Hofmann of the Auschwitz Erkennungsdienst, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

“Those who struggled to start menstruating again, conceive or stay pregnant wondered if they were the only ones,” she said.

Although the study’s sample is small, it is illuminating concerning struggles with infertility. Ninety-eight percent of the women interviewed were unable to conceive or carry to term their desired number of children. Only 16% of the women were able to carry more than two babies to term. The majority had one or two children. None had more than four live births.

Only 16% of the women were able to carry more than two babies to term. The majority had one or two children. None had more than four live births

The percentages of miscarriage and stillbirth among these women were considerably higher than normal when compared to American and Canadian women of that era. In speaking with Kleinplatz, some survivors, due to language issues, conflated miscarriages with stillbirths. This muddles the picture somewhat, but it is still clear that the pregnancies of this sample of women resulted in miscarriage at a rate of 24.4-30% and stillbirth at a rate of 6.6-7.6%.

Secondary infertility among the women created long stretches between pregnancies resulting in live births. For six of the women in the study, 10-16 years passed between successful pregnancies.

Three women suffering from typhus lie closely packed together in one of the huts at liberation of Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp, April 1945. (No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit, Oakes, H (Sgt), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Notably, only three of the 93 women interviewed had as many children as desired. Two of them had refused to eat the concentration camp rations, and one spent the Holocaust years hiding in forests (and never lost her period).

In seeking a possible reason why so many of the women — who would have been teenagers during the war — had trouble carrying babies to term, the study mentions “research done with female monkeys suggesting that if exogenous progestins are administered during adolescence, the resulting changes to the structure of the uterus may enable mature females to conceive later on but render their uteruses incapable of carrying the fetus to term… Although experimentation on humans would be unethical, observational research on women seems to indicate that the pattern holds true.”

Kleinplatz said she searched for medical literature from the post-war decades on this common and devastating infertility among survivor women and found none.

Olga Czik Kay (Courtesy of Yad Vashem)

“No pattern emerged publicly in the literature about these survivor women not only because was it socially unacceptable to speak about it, but also because physicians did not take comprehensive sexual and reproductive histories of their patients,” Kleinplatz said.

“I teach students to take these histories, but to a large extent, this is still not taught in medical schools. In fact, there was more emphasis on it in the 1970s and 1980s than there is now,” she said.

Hungarian Holocaust survivor Kay recognizes her fortune. She knows other women who were in the camps who did not have the families they dreamed of. She asked a friend who was also in Auschwitz and was unable to conceive if she would agree to an interview with The Times of Israel.

“She said she can’t. It’s too painful,” Kay said.