Opinion: End Verse, End-Times

Whether the world ends with a bang or a whimper, it will be an event without a witness

Published Date – 12:45 AM, Fri – 24 February 23

By Pramod K Nayar

Hyderabad: In Wallace Stevens’ ‘Sunday Morning’, the protagonist ‘feels the dark/Encroachment of that old catastrophe’. The poem ends on a note metaphorising mass extinctions:

in the isolation of the sky,

At evening, casual flocks of pigeons make

Ambiguous undulations as they sink,

Downward to darkness, on extended wings.

Stevens’ ending with its ‘ambiguous undulations’ has a softness that is in sharp contrast to TS Eliot’s declaration in ‘Hollow Men’: ‘this is the way the world ends/not with a bang but with a whimper’.

Such poetry is the equivalent of apocalyptic fiction about the end-times.

End-times and Verse

Arguably, one of the most popular representations of end-times is Lord Byron’s ‘Darkness’ (inspired by the 1815 Mount Tambora explosion in Indonesia which altered weather patterns all over the world), which offers an image of a new ice age:

The bright sun was extinguish’d, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air;

In this apocalyptic winter

The habitations of all things which dwell,

Were burnt for beacons; cities were consum’d,

And men were gather’d round their blazing homes

To look once more into each other’s face;

Humans and other lifeforms are victims to this catastrophe:

vipers crawl’d

And twin’d themselves among the multitude,

Hissing, but stingless — they were slain for food.

Even dogs assail’d their masters, all save one,

And:

The world was void,

The populous and the powerful was a lump,

Seasonless, herbless, treeless, manless, lifeless —

A lump of death…

Byron concludes with:

The winds were wither’d in the stagnant air,

And the clouds perish’d; Darkness had no need

Of aid from them — She was the Universe.

If Byron speaks of a wintry end, so does Robert Frost:

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

In WB Yeats’ ‘Second Coming’ a ‘rough beast slouches towards Bethlehem’, the beast of the apocalypse.

In Czesław Miłosz’s ‘A Song for the End of the World’, it is a quiet end:

On the day the world ends

A bee circles a clover,

A fisherman mends a glimmering net.

Happy porpoises jump in the sea

And ‘those who expected lightning and thunder/Are disappointed’. So people

Do not believe it is happening now.

As long as the sun and the moon are above,

As long as the bumblebee visits a rose,

As long as rosy infants are born

No one believes it is happening now.

Often, the poetry of end-times employs the metaphor of emptiness/emptying.

Houses but not Homes

A census taker in Robert Frost’s poem of the same title approaches a solitary house in the middle of nowhere. He finds the house is ‘an emptiness flayed to the very stone’. Puzzled, he explores the house: ‘No lamp was lit. Nothing was on the table/The stove was cold’. There are no people: ‘I saw no men there and no bones of men there’. He wonders what to do ‘about the people not there’. His profession itself becomes redundant with each year:

The melancholy of having to count souls

Where they grow fewer and fewer every year

Is extreme where they shrink to none at all.

He concludes that, at least for his job, he needs to have life go on: ‘It must be I want life to go on living’.

Walter de La Mare’s justly famous, ‘The Listeners’, opens with

‘Is there anybody there?’ said the Traveller,

Knocking on the moonlit door;

Says de La Mare:

But no one descended to the Traveller;

No head from the leaf-fringed sill

Leaned over and looked into his grey eyes

But the house has ‘a host of phantom listeners’ who ‘stood thronging the faint moonbeams on the dark stair’. He finally leaves, and ‘the silence surged softly backward’.

Langston Hughes in ‘Empty House’ finds the emptiness hell: ‘in the empty house/I found an empty hell’. In this empty house, says Hughes, there is more woe than the ‘wide world’.

Such thought experiments may be read as allegories for an Earth devoid of humans, on the lines of Alan Weisman’s The World Without Us. The houses are what will survive of us when we are gone. Except of course, one has to ask, whether ‘house’ itself is a metaphor for something, a legacy, perhaps. If there are survivors, what do they make of such empty houses that are no longer homes? Who witnesses what happens afterwards?

Witnesses and Prophets

The absence of people does not imply an absence of life: for there are ghosts, revenants and other forms that witness the end-times

In Wallace Stevens’ ‘The Snowman’, the snowman is the sole witness to winter’s magnificence, there is no human witness:

For the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the

nothing that is.

Wise witnesses know that end-times do not require, as Miłosz puts it, ‘lightning and thunder’. The world can end quietly:

Only a white-haired old man, who would be a prophet

Yet is not a prophet, for he’s much too busy,

Repeats while he binds his tomatoes:

There will be no other end of the world,

There will be no other end of the world.

In Mary Oliver’s ‘I Found a Dead Fox’, the speaker sees a dead fox and lies down next to the body: ‘when I crawled in/and lay down… and touched the dead fox’. Then

the fox

vanished.

There was only myself

and the world,

and it was I

who was leaving.

And what could I sing

then?

It is the human who disappears here.

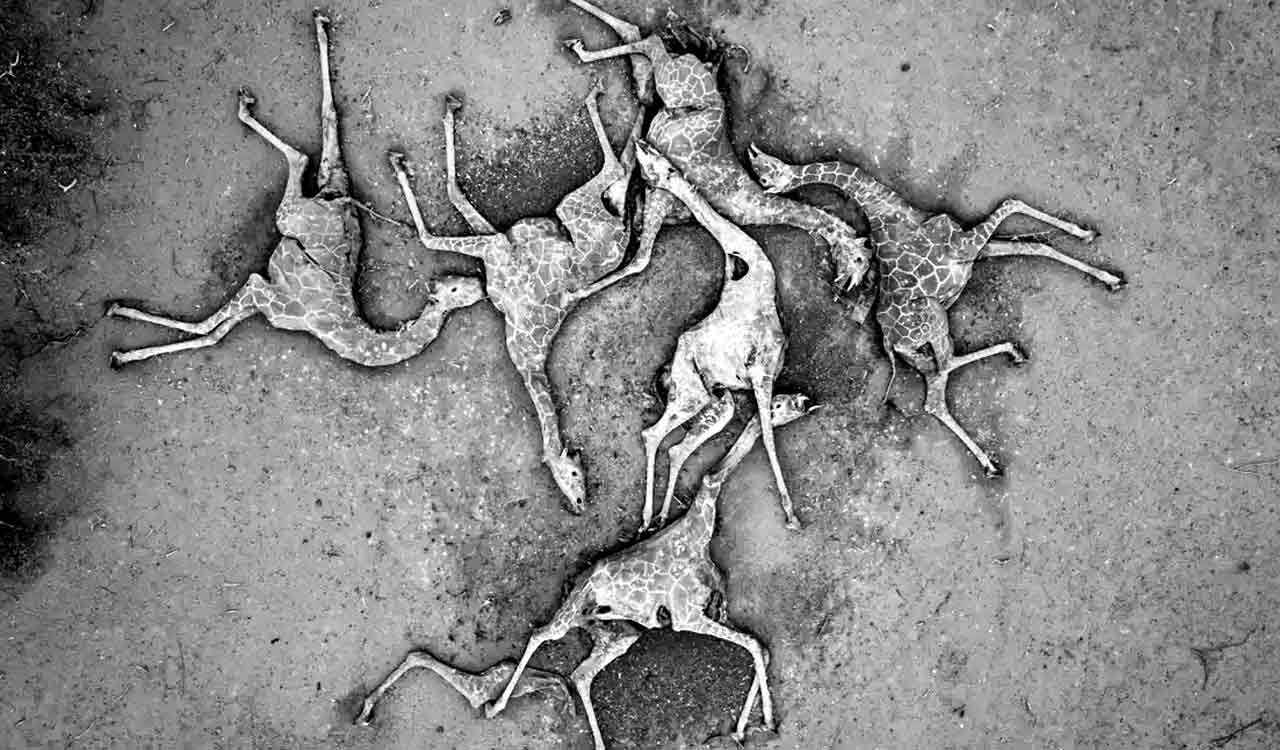

From Byron to Miłosz and Oliver, poetry of and in the end-times carry signs of the end-times in terms of death and dying, of empty homes and dark worlds, of species gone and going.

Perhaps the end of the world would be an event without a witness.