NEW YORK — In late 1941, thousands of Latvian Jews were rounded up and marched through the Rumbula forest outside Riga to be shot by the Nazis. Among them were the mother, grandmother and sister of artist Boris Lurie.

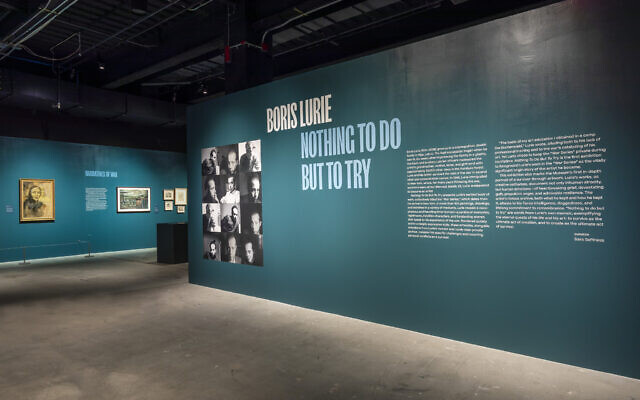

Now, 80 years later, an exhibition at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City is presenting an “in-depth portrait” of Lurie through the works he created in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust. The exhibit, titled “Boris Lurie: Nothing To Do But Try,” runs through April 2022.

The Rumbula massacre occurred on November 30 and December 8, 1941, two days during which some 25,000 Jews were murdered by the Nazis in the Latvian forest. The massacre is one of the largest to have been conducted during the Holocaust, along with the mass murder at Babyn Yar in Ukraine. Of those who were led to the Rumbula killing site, only three were known to have survived the Holocaust.

“Boris Lurie’s life is kind of defined as pre-Rumbula and post-Rumbula and very much responsive to this foundational trauma of his,” Sara Softness, curator of the exhibit, told The Times of Israel last week during a tour through the installation. “He has rarely had this much of his early work on view.”

Those familiar with Lurie almost certainly know him for his more radical and provocative work from the 1960s mixing pornographic and Holocaust imagery, which he created as part of the No!Art movement co-founded in a defiant rejection of the contemporary art scene. But Lurie’s earlier pieces, those that reflect his deep trauma from the concentration camps, remained somewhat unknown and have never been exposed in his lifetime, perhaps too personal for him to show.

Walking through the exhibit, visitors can almost feel the bitter cold of Latvia and the dreary, anxiety-inducing ghetto. Nearly 100 nightmarish depictions of barbed wire, gloomy buildings and thin extraterrestrial-looking figures in striped pajamas with green-tinted skin and zombie-like expressions constitute much of Lurie’s “War Series.” Some of the pieces are made with pastels, some with oil on canvas, and others with pencil, scribbled on pages clearly ripped from one of his journals, smudged, folded and preserved.

Sara Softness, curator of ‘Boris Lurie: Nothing To Do But To Try,’ at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City, December 2021. (Danielle Ziri)

“He’s dealing with ambiguity, emotional ambiguity: feelings of guilt, grief, anger, fear,” Softness said. “A lot of the works that come out of this period are these unbelievable upside-down, disintegrating figures, shadows, skeletal surreal figures. It really speaks to this nightmare.”

Lurie came from a wealthy upper-middle-class Russian family who had come to Latvia when the Soviet Union was founded. In June 1941, when Lurie was only 16, the Nazis invaded Riga. Within a month, synagogues were burnt, Jews were arrested, the wearing of yellow stars became mandatory.

Lurie, whose mother was murdered in the Rumbula massacre, was saved by his ability to work: By the time of the massacre he had already been sent to the work camp in Riga, also known then as the “small ghetto,” along with his father Ilya. The two become work slaves for the rest of the war, moved several times within Latvia and to camps in Poland and Germany. When liberation came, they managed to survive the last killings. Lurie briefly worked in Europe for the United States Counter Intelligence Corps — a precursor to the CIA — and in 1946, the pair finally immigrated to New York City, where Lurie’s sister lived. That was when Lurie started painting his then still-fresh recollections of the Holocaust, as if to record them before they evaporated from his memory.

“This is not an example of artwork made in the camps or anything like that,” Softness said. “The minute he gets to New York he sort of unloads this cathartic process through the artwork that he makes.” Lurie, she said, has “always been really dogged about remembrance and about recording.”

Still shot from the 2002 documentary ‘A Visit With Boris Lurie,’ by Matthias Reichelt. (YouTube)

“That has always punctuated his life, behaviors and habits,” she added. “He kept everything.”

The exhibit indeed presents a mix of art and documentation. Among some of the most notable pieces is a portrait of Lurie’s mother, which he titled “Portrait of My Mother Before Shooting.” It was his last image of her. The muted portrait shows a slim-faced woman in a collared coat, a hopeless look in her eyes.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Softness said. “He kept this portrait his entire life. It was his most prized possession.”

‘Portrait of My Mother Before Shooting’ by Boris Lurie, shown at the exhibit ‘Nothing To Do But To Try’ at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City, December 2021. (Danielle Ziri)

“It was his mother who really ensured Boris’s survival, which caused him guilt for the rest of his life,” the curator added. “It was she who told him to go to the work camp.”

Under a glass counter is also a letter Lurie sent to the editor of The New York Times on October 26, 1950, in which he wishes to bring awareness to the Rumbula massacre.

“It will hardly be remembered, except unfortunately by a very few, that December 8th stands for anything but the day of the attack on Pearl Harbor […] As Japanese planes dropped their first loads on the American base, 25,000 Jewish children women and old people were being murdered by platoons of Germans and Latvians with approval of the local citizenry,” he writes.

‘Roll Call in Concentration Camp’ by Boris Lurie, shown at the exhibit ‘Nothing To Do But To Try’ at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City, December 2021. (Courtesy of the Boris Lurie Art Foundation)

The Museum of Jewish Heritage’s exhibition is not just focused on Lurie’s visual work, but also on his words: texts, letters, poems are presented for visitors to read. In 1975, he returned to Latvia for the first time since the war. The visit is deeply emotional.

“He is really beside himself trying to reconcile this place that he imagined, the place that has existed in his nightmares and loomed over his life and to see it in real life and see how unremarkable it really is,” Softness said.

The trip prompts Lurie to write a memoir about his experiences. Softness said the choice of title for the exhibit came from that book. “There is a passage where he is actually speaking about learning to become a painter. […] he wrote ‘there was nothing to do but to try,’ and I thought that was an incredible parallel to his experience as a survivor,” she said.

‘Boris Lurie: Nothing To Do But To Try,’ at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City. (Courtesy)

Lurie died in 2008 and is buried in Haifa, Israel. He never had any children and apart from distant cousins, has no known remaining family. All of the work presented in New York is on loan from the Boris Lurie Art Foundation, which he endowed before he died. It is run by his friend Gertrude Stein, a woman in her 90s who has made it her mission to ensure his legacy to “document the history which would keep the memory alive for a more peaceful future.”

‘The Liberation of Magdeburg’ by Boris Lurie, shown at the exhibit ‘Nothing To Do But To Try’ at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City, December 2021. (Courtesy of the Borie Lurie Art Foundation)

For Softness, making sense of this work, which had been kept private for decades, was an “honor.”

“Not only is it a way of accessing a survivor’s story which is what the museum is all about, but it does so pretty profoundly with one survivor and it is so emotionally profound you can’t help but understand this person’s experience,” she said. “It’s really difficult to work on a project like this. I have to kind of desensitize to a certain degree, but it’s been the feedback of people who have come to see it that really has made it the unbelievable experience it has been.”