Israeli scientists say they managed to slash the incidence of breast cancer relapse in lab mice by 88 percent by adding a second drug to chemotherapy.

The team of academics from Tel Aviv University say inflammation in the body in response to chemotherapy can actually nurture renegade breast cancer cells that dodge the treatment. The use of an inflammation blocker in conjunction with chemotherapy appears to counter this effect, thus lowering the chances of the cancer returning.

The peer-reviewed research by biologist Prof. Neta Erez and her team was recently published in Nature Communications.

The academics believe that the method can be adapted for humans, though they expect the extra research to take 5-10 years.

Erez has spent years investigating the collateral damage that chemotherapy can cause.

Hair loss is well known, but lesser known is the growing body of research on chemotherapy, in some cases, raising the risk of metastatic relapse. This means the return of cancer caused by cancer cells that traveled away from the tumor and survived elsewhere in the body during chemotherapy.

In the research, the animals were injected with tumors that mimicked human breast cancer, and like human patients, then had the tumors removed and were given chemotherapy. “Among the mice who had only chemo, some 52% had extensive metastatic relapses, but among those who receive inflammatory blockers, only 6% relapsed,” Erez told The Times of Israel.

“We are excited about our findings in mouse models, and hope they can be translated to develop better therapeutic strategies for patients, to alleviate the adverse effects of chemotherapy and to prevent breast cancer metastatic relapse.”

Left to right, Tel Aviv University researchers Dr. Nour Ershaid, Prof. Neta Erez and Lea Monteran. (Courtesy of Tel Aviv University)

Erez explained that the research, conducted with Lea Monteran, Dr. Nour Ershaid, Yael Zait, Ye’ela Scharff, and others, started as an observation of how chemotherapy can sometimes harm patients.

“Chemotherapy is used to treat many cancers, and the good news is that it kills cancer cells, but chemo can be a double-edged sword as it’s not a very sophisticated weapon,” Erez said,

“This is the case because it doesn’t only kill cancer cells but also causes a lot of collateral damage. It kills even healthy cells that are dividing, hence the hair loss.

“So, while effectively killing cancer cells, chemotherapy also has some undesirable and even harmful side effects, including damage to healthy tissues. The most dangerous of these is probably internal inflammations that might paradoxically help remaining cancer cells to form metastases in distant organs. The goal of our study was to discover how this happens and try to find an effective solution.”

The team concluded from its observations that breast cancer commonly returns after cells hide out in the lungs, which become more hospitable to the cells as a result of chemo.

“What we showed is that tissue damage induced by chemotherapy instigates an inflammatory response in lungs,” Erez said. “Then, if small amounts of breast cancer cells are left in the lung, this inflammatory response triggered by chemotherapy ironically makes these cells thrive, and creates a hospitable environment for cells which then go on to cause a relapse of breast cancer.”

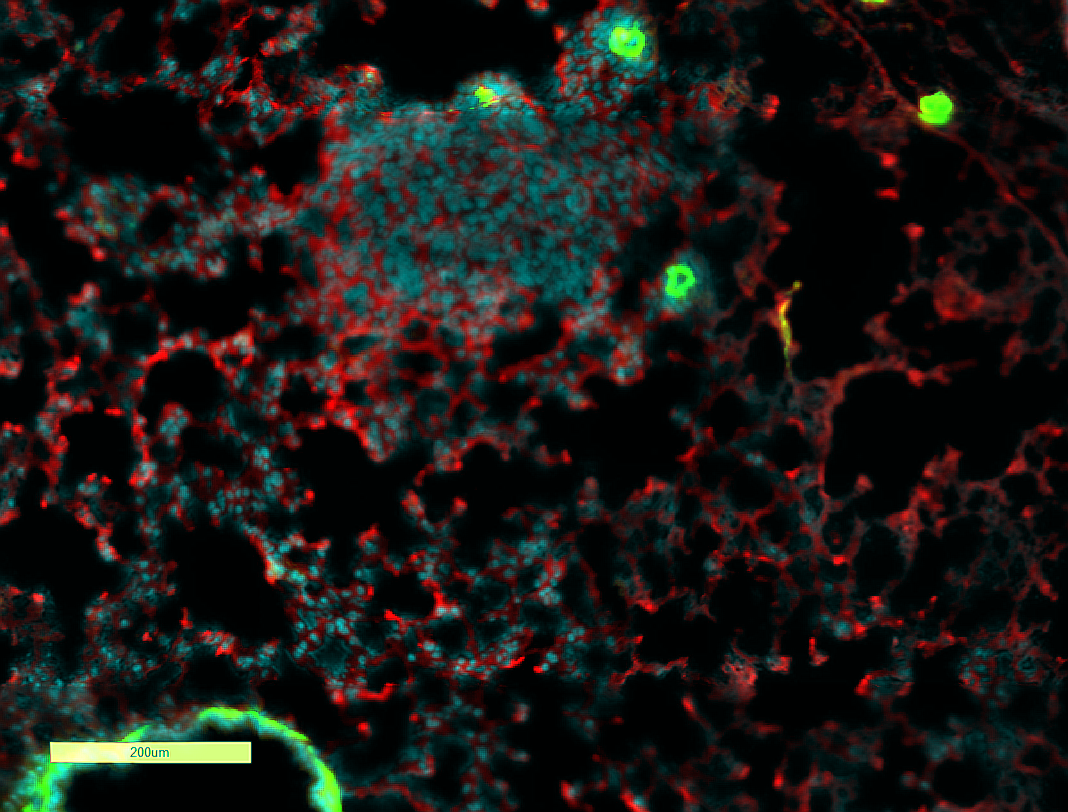

Image from a mouse in the Tel Aviv University lab behind the new breast cancer research, showing cancer cells in cyan and, in red, the proteins causing inflammation which in turn creates a hospitable environment for the cancer cells. (Lea Monteran)

They found that the tissue damage caused by chemotherapy instigated an inflammatory response in fibroblasts, which are cells found in connective tissues. These activated fibroblasts start secreting proteins that cause an influx of immune cells from bone marrow to the lungs. The immune cells, in turn, bring about an inflammatory process that creates an environment friendly to cancer cells.

After identifying proteins that are secreted by fibroblasts, the team used an existing drug which is known to stop the proteins from causing inflammation, but which had not previously been known to have value in stopping metastatic relapse.

After more research and testing, if the blockers are effective with humans, they could potentially be given to patients with chemotherapy doses.